A Silent Revolution in Your Kitchen: Why Composting is the Most Radical (and Easiest) Thing You Can Do

There is a specific kind of "itch" we all share: that uncomfortable feeling when you see a plastic bottle in a forest or a candy wrapper on the grass. It feels like a glitch in the matrix, and you feel the urge to bend down and pick it up.

Food scraps: organic life on pause and waiting to be recycled

That small act of cleaning up litter is often our gateway to environmentalism. During my first cleanup in 2011, two lightbulbs went off for me: first, that these items simply don’t belong in nature; and second, that they aren't "trash," but lost resources that belong back in an industrial or productive loop.

Once your eyes see resources where others see trash, it’s hard to ignore them. They can’t be unseen, and it’s actually quite a magical feeling. I invite you to apply that same newfound lens to another part of our daily waste that we’ve been taught to ignore: it’s time to look inside our own homes and rescue our organic waste from the places it doesn't belong. Just as a bottle doesn't belong in a river, a banana peel doesn't belong in a plastic bag or a kitchen sink.

It is not trash. It is life on pause waiting to be circulated back into nature.

The Illusion of "Away" and the Biodegradable Lie

Most people in the developed world live under a comfortable, hygienic illusion tied up with a double knot: the plastic garbage bag. We have been taught that we can throw away and discard anything we no longer find a use for. The logic is simple: if it no longer serves me, it shouldn't occupy space in my home or my mind. We view waste as something undesirable that must vanish from our sight. We put it on the curb, a truck passes by, and magically, the problem is no longer ours. 'Problem solved,' we think.

But have you ever stopped to think where 'away' actually is?

I’m sorry to break it to you, but there is no such place as 'away.' We move the trash out of our sight, but the reality is that the problem hasn't disappeared—it has only just begun.

If we were to rip open that bag and analyze what we are throwing away, we would be in for a shock. Although our minds picture plastics, cans, and glass, the reality is that up to 50% of municipal solid waste is organic. Food scraps, peels, tea bags, coffee grounds, dirty paper.

But here is the most absurd, infuriating part: organic matter is nearly 80% water.

This means those giant, smoke-belching trucks are essentially taking water for a ride around the city. We are burning fossil fuels and spending millions in tax dollars just to transport humidity from your kitchen to a hole miles away. It is a logistical nightmare—but the real tragedy isn't the transport; it’s the destination.

"But if it's organic, it biodegrades anyway, right?"

I get it. We’ve all been there. We’ve been told this millions of times. But this might be one of the most dangerous conceptual mistakes. We believe that throwing an apple core in the trash bag is harmless because "it's natural".

Think again. For organic matter to transform into soil (to biodegrade correctly to the basic chemical elements of life), it needs air. It needs oxygen. However, when a banana peel, or a newspaper arrives at the landfill in a plastic bag, and gets buried under tons of other waste, squeezed inside even more plastic bags, there is no air.

The landfill is an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment and the microorganism that are the ones responsible for the “bio” part of biodegrading, can’t live. In the end, what happens is that in the landfill the organic matter doesn't biodegrade.

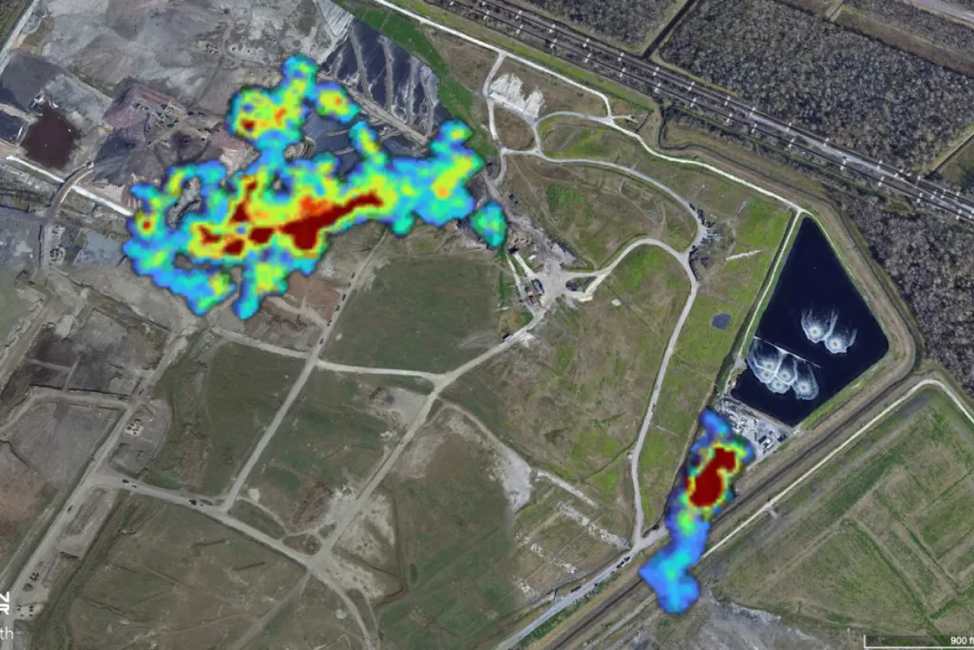

Methane plumes observed at a Louisiana landfill during the study. More than 14% of U.S. methane emissions were reported to have come from landfills in 2021.

This is exactly what William Rathje, the father of 'Garbology,' discovered when he began excavating American landfills. He expected to find degraded matter; instead, he found 'mummified' waste. He unearthed 20-year-old heads of lettuce and newspapers from the 1950s that were still perfectly legible.

"The dynamics of a modern landfill are very nearly the opposite of what most people think... In reality, a landfill is not a vast compost pile. It is a vast mummifier." — William Rathje & Cullen Murphy[1]

Without air, the biological clock stops: Instead of becoming life-giving soil, our food scraps turn into a source of toxic leachate and methane (CH4). Methane is a greenhouse gas significantly more potent than carbon dioxide (CO2) in its capacity to heat the atmosphere in the short term. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), municipal solid waste landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the United States.

William Rathje, Garbologist - Talkin Trash 🙂

The equation is simple and brutal: Not composting is not neutral. Throwing organics in the trash is unfortunately actively contributing to pollution in our atmosphere.

The Grinder Trap: Sewage Economy vs. Circular Economy

Perhaps you’re thinking “Okay, but my organic waste is going down the drain, not in a plastic bag, not that bad, right?”. And I get the appeal. The kitchen sink garbage disposal is marketed as the ultimate convenient food waste management solution: "I grind it, it goes down the pipe, and it’s gone."

Do food scraps belong in a sink “garbage disposer”?

I call this the "Flush-and-Forget" Economy.

But we need to be clear: sending food down the drain is not a circular solution; it is an energy-intensive, sewage-based detour.

Let’s have a look to what happens after we push that button, as “there’s no “away”, the food doesn't vanish in this case either, it just liquidifies, creating a ripple effect of hidden environmental costs:

● It Leaks Methane: Food starts rotting the second it hits the sewer, releasing methane that vents out of manholes and street pipes directly into the air long before it reaches any treatment plant.

● The "Dirty Water" Paradox: We use liters of perfectly clean water just to wash away a "problem." This creates a "liquid soup" that is incredibly hard to clean. According to a 2023 study (Kim et al.), the more food we flush, the more electricity and chemicals the city has to burn just to "un-dirty" that water in water treatment plants.

● It Kills the Nutrient Cycle: Nature designed food scraps to be soil, not sewage. The grinder takes a high-value nutrient and turns it into "sludge"—a waste product that usually ends up incinerated or buried anyway.

Now that we’ve exposed the environmental cost of both the garbage bag and the 'flush-and-forget' method, let’s explore a much better alternative solution, that doesn't just try to make waste disappear, but instead find ways to bring life back to earth: composting.

Enter Composting

So, what is compost? In case you don’t know, think of it as nature’s original recycling system.

In nature, the concept of 'trash' simply doesn't exist. Throughout the cycle of life, everything is a nutrient for someone else; everything is life. There is nothing that doesn't serve a purpose. The very idea of 'waste' is a human invention. If we discard a rotten fruit, a bird can eat it. What the bird rejects, a worm eats. Then bacteria... then fungus... in the end the manure of each organism becomes energy for another organism to grow. When all the matter has been digested by some organism and it’s back to nature’s basic elements, plants can absorb those nutrients to create new leaves and fruit, and the cycle begins again.

It’s the original circular economy. When we talk about cycles, we’re only trying to mimic nature.

Composting it is simply the act of taking our organic "waste" and facilitating this virtuous cycle instead of polluting.

Busting Myths: It’s not Rocket science

I know why you haven't started yet. I hear the excuses every day: "I don't have time," "It's too difficult," "It’s gross," "I live in an apartment."

Let me stop you right there. Composting isn’t hard. It might take a little learning—as with anything new—but you definitely don’t need a PhD in biology, and it can be as easy as you want it to be.

Strictly speaking, we don’t "do" the composting ourselves. Nature wants to decompose things. We just have to let it happen and stay out of the way. Composting is simply about creating the right conditions for the decomposers to do their job.

On the ground or in a bin? A pile or a hole? Vertical or horizontal? A rotating system or a stationary one? With or without earthworms?

There are many different composting methods, but in all of them, the real magic is performed by microorganisms—those microscopic workers that thrive when the environment is right. Our only task is to act as stewards, maintaining the conditions where they feel "at home" so they can get to work.

Let’s review quickly two of my favorite and easiest methods:

The "SLANT" Method (Lazy Composting)

Scenario A: You Have a Garden (The Deep Hole Method)

If you are lucky enough to have a piece of land or a backyard, you have won the lottery. Forget the tumbling plastic bins. There are lots of outdoor composting techniques, but my favorite method for you, that requires the least maintenance is: The Deep Hole (with lid).

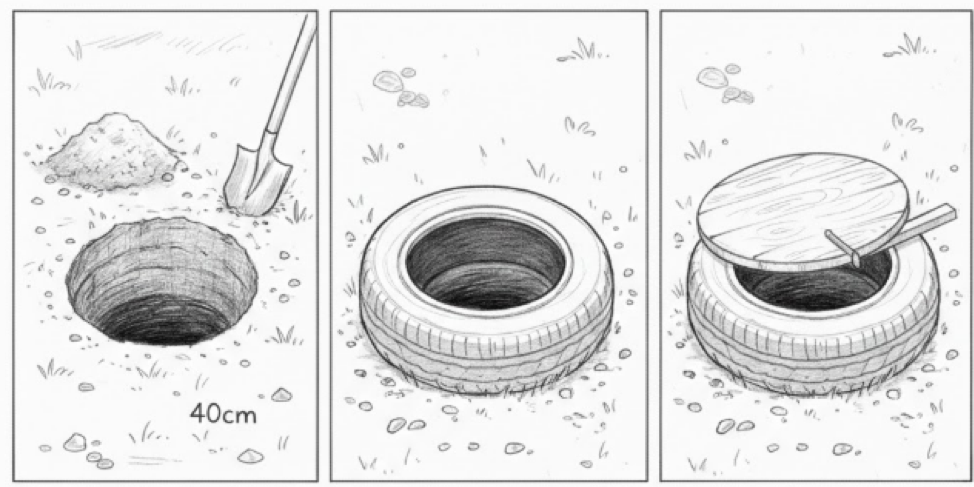

A simple way to design an in-ground composting receptacle

How to do it?

The Hole: Dig a hole in the dirt. Geometry is key. It must be deep (1, 2, or 3 meters if you can manage it) but with a narrow mouth at the surface (about 40 or 50 cm wide).

Why this shape? Depth gives you massive storage capacity (it can take years to fill up). The narrow mouth reduces the surface area exposed to the outside air, which minimizes smells and prevents animals from entering.

The Lid (Crucial): The mouth must be covered. Non-negotiable. You can use heavy wood, or a tile. Even an old tire can be reused for this. It must be easy for a human to open, but impossible for a dog.

The Process: Open lid. Drop scraps. Close lid. Done.

Easier and cheaper than throwing it in the trash.

With this method, you don't worry about anything. The soil surrounding the hole regulates everything; nature balances itself. It is the most resilient system in existence. Why aren’t we all doing this? That’s what I’m wondering.

Scenario B: You Live in an Apartment (The "SLANT" Rule)

If we aren’t that lucky, then composting requires a very very small but rewarding learning curve. Here, the game changes. Since we aren't connected directly to the earth, we are the "gods" of that little closed ecosystem inside a bucket or bin. We don't have the earth's buffer, so we need to learn a little. It’s not hard, we just need to befriend the rules that welcome life.

If we throw just fruit peels into a sealed bucket, they will rot, right? Because that’s not composting.

Let’s clear something up: composting should not stink. If your bin smells bad, it’s not because composting is 'gross'; it’s because it’s giving you feedback. A healthy compost pile isn't too wet, too dry, or imbalanced—it’s a living ecosystem that just needs the right ingredients in the right amounts.

To be a successful 'slacker' composter, you don't need to be a scientist; you just need to understand what the system requires so that when something feels off, you know exactly what’s missing or what’s in excess. To troubleshoot like a pro and never forget which variables to control, here’s my teaching rule, the S.L.A.N.T. mnemonic of the compost needs:

● S - Structure (Carbon / "The Browns"): This is the skeleton of the compost. Dry leaves, cardboard, egg cartons. Carbon absorbs excess moisture and provides structure so air can pass through. Golden Rule: For every pot of kitchen scraps, add some dry "browns", it doesn’t have to be exact, but don’t miss on the “S”.

● L - Liquid (Moisture): Life needs water, but not a swimming pool. We are looking for the "wrung-out sponge" texture: damp to the touch, but not dripping. Too wet = rotten smell. Too dry = nothing happens.

● A - Air (Oxygen): Our decomposer partners breathe oxygen. If the compost compacts, they suffocate, and the bad-smelling anaerobic bacteria take over. Solution: Stir or mix on demand.

● N - Nitrogen (Nitrogen / "The Greens"): Your waste. Peels, coffee, tea, vegetable, food scraps. This is the food and energy.

● T - Temperature: Remember that life follows the thermometer; it hibernates in the cold and thrives in the heat. Winter is slower. Spring and summer it’s a microbial party.

To keep it safe and simple—especially when you are just starting and we want to be a success—follow this quick-reference guide:

● 🔴 RED: Stop (Avoid these)

○ Meat and Fish

○ Dairy and Eggs

○ Oily or Baked Goods

● 🟡 AMBER: Caution (Use in moderation)

○ Citrus: Orange or lemon peels are acidic.

○ Cooked Grains: Small amounts are okay, but not much.

● 🟢 GREEN: Go! (The Staples)

○ Fruit and Veggie Scraps

○ Coffee Grounds and Tea: just be aware that 90% of tea bags have plastic inside.

○ The "Browns"

If you respect the SLANT rule and the traffic light system, you can compost in a studio apartment without a single bad smell.

Compost as a Mirror and Therapy

Beyond the technique and the science, composting has a profound impact on our personal lives if we let it. It is a literal "grounding" exercise. Putting your hands in the soil, stirring, smelling the humus when it’s done... it reconnects us with rhythms that modern life has made us forget. Nature does not rush, but it does not stop.

I like to think that compost reflects us.

It is also a brutally honest indicator of our health and eating habits.

● If your bin is a rainbow of banana peels, apple cores, broccoli stems, avocado skins, and vibrant colors, it is very likely that your body is receiving those nutrients too.

● If, however, days go by and you have nothing to throw in the compost (or just coffee and napkins), it is an alarm bell. It means you are eating too much processed food, too much meat, too much takeout or delivery with plastic packaging, and not enough real food.

A healthy compost pile is usually synonymous with a healthy diet. Taking care of your compost is, indirectly, a reminder to take care of yourself.

The Magic of "Bugs": Changing the Perspective

Composting also changes your mindset regarding insects. We go from seeing them as enemies to seeing them as collaborators. We put down the insecticide and pick up the magnifying glass.

Bugs will appear - and that is okay. On this note, I want to give an honorable mention to the Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens).

Unlike the common housefly (the annoying one that lands on your food), the adult Black Soldier Fly does not have a mouth. It doesn't eat, doesn't bite, doesn't buzz around. It only lives to reproduce.

But its larva... its larva is a perfect biological machine. It is one of the most voracious decomposers in nature. They eat faster than earthworms and reduce waste volume in record time. Globally, they are already being used on an industrial scale to eliminate city waste.

If you see a big, grey, segmented larva in your compost that’s really ugly and disgusting: it’s great news! Do not kill it! It is the elite demolition squad. It is working for free for you.

If you don’t like bugs, skip this recommendation, but if you can see through the lens of awe, there are incredible time lapses of Black Soldier Fly larvae eating whole foods in hours:

Imperfect Activism: The Manifesto

In closing, let’s address a dangerous trap in the environmental movement: the "All or Nothing" mindset. That feeling that if you aren't Zero Waste, Vegan, and perfect, you are a hypocrite.

I want to destroy that idea right now. Perfection is the enemy of action.

● It is okay to compost only in the summer if winter makes you lazy.

● It is okay to compost only the "easy" stuff (coffee and fruits) and throw away the rest if you are overwhelmed with work.

● It is okay to take a break.

Imagine if everyone composted just 10% of their waste. The collective impact would be infinitely greater than that of a tiny group of people doing it 100% perfectly. We don't need environmental martyrs; we need millions of people making small, imperfect changes.

The world doesn't need you to be perfect. It needs you to start.

Dare to get your hands dirty. I promise you, it’s a one-way trip.

Are you ready to turn your "trash" into life?

References

[1] Rathje, W. L., & Murphy, C. (1992). Rubbish!: The Archaeology of Garbage. HarperCollins.